20. Network Effects: Not Just About Size 🦄

Network effects depend on density, the core transaction, and a social mechanism, not just network size.

Happy Sunday 🥞

I’m on the hunt for my next Product role. I’m ideally looking at fintech or healthcare. If that’s you, I’d love to chat. Or, grab me on LinkedIn. I’m always open for a conversation!

In other news, my kids ran a lemonade stand last weekend. A patron paid $5 for a single cup; the advertised price was $1. Ah, to be young. 😂

Enjoy today’s ideas around network effects. See you next week!

Cheers,

Jeremey

Thanks for reading another edition of Strategy Meets World – a weekly deep dive into building products that serve customers and the business.

Enjoy this edition? Smash the ❤️ icon. New here? Subscribe to get future issues in your inbox every Sunday morning.

You Need More Than Size to Have Network Effects

After reading Modern Monopolies, I went down a rabbit hole thinking about moats and competitive advantages. Specifically, network effects since they’re “the strongest economic moat of all.”

As a quick recap, products have a network effect when each new user makes the network more valuable for all other users. Facebook (in the early days) is a classic example. Slack is a more recent one. Venmo is my favorite.

A network effect is a strategy for both growth and defense.

For growth, a network effect means more organic growth and a lower CAC. I’m incentivized to tell you about Facebook so I can interact with you.

For defensibility, a strong network effect increases the switching cost. The value is in the network itself, not the software. Competitors can copy the later, not the former. I can move myself from Twitter X to a service like Mastodon, but if I’m in the minority, I’ll feel the pull back to where everyone else is hanging out.

When discussing network effects, the most obvious characteristic is size. All else equal, larger network tend to exhibit greater network effects (aka Metcalfe’s law). But, as I’ve been reading and thinking more, I’ve come to realize that size is only one of a few important characteristics. And maybe not even the most important one.

Here are three attributes we’ll walk through today although I’m confident there are more:

Network Density

Core Transaction That’s Constantly Improving

Social Mechanism

Network Density

Smaller, denser networks > larger, diluted ones.

The mistaken assumption in network effects is that all potential connections are created equal. Therefore, larger networks always win. In reality, not all potential connections are relevant.

Let’s take OpenTable as an example. I’m currently located near Denver, Colorado. I’m very interested in new restaurants joining the platform around the Denver area. I’m not at all interested in restaurants in Dallas or Portland.

The value of network effects comes from potential transactions, not potential connections.

This is why platforms that exhibit strong network effects often start with a small, targeted audience. In his book The Cold Start Problem, Andrew Chen refers to these as “atomic networks.”

Facebook was famously only open to Harvard students. Uber first started in San Francisco and then strategically opened in individual cities. Strava exclusively started with the cycling demographic despite having a much larger vision for athletics. (They’ve jokingly described their initial target customer as a “mamil” - middle age man in lycra.)

Great networks have to start with a concentrated group of users that are likely to transact and grow from there.

Core Transaction That’s Constantly Improving

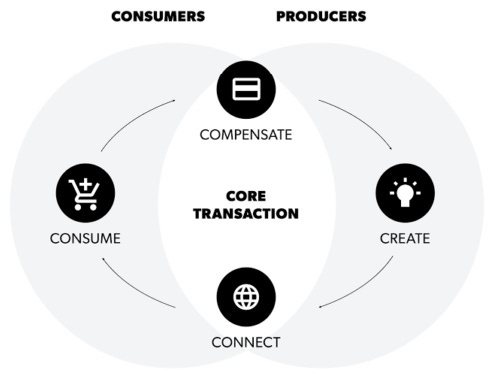

The “core transaction” lies at the heart of any network. Here’s Modern Monopolies again:

The core transaction is the platform’s “factory”—the way it manufactures value for its users. It is the process that turns potential connections into transactions.

Facebook Marketplace is useless if users don’t actually buy and sell goods. Similarly, Venmo loses its luster if no one sends money back and forth. This feels obvious, but it’s also easy to lose focus on the core transaction and pursue growth at all costs instead. Take Vine, for example.

Vine took the world by storm back in 2013. They were growing faster than Instagram or YouTube. Twitter bought the app before it even launched for $30 million. In 2016, with 200 million active users, Vine shut down.

broke down one part of the meteoric rise and fall - they failed to innovate around the core transaction:…Vine failed to innovate and meet demand, we can see:

They did nothing to compensate, meaning the incentive to create was diminishing

They also limited creation by not leaning into the experimentation tools Viners wanted

Connecting with creators/content became harder, meaning consuming content was limited

Compare this to Strava - an app that continues to evolve the core transaction.

When Strava launched, you could only upload workouts from Garmin devices, and you had to plug the device into your computer to do so. Clunky. Since then, they’ve only made it easier - hundreds of integrations, native iOS apps, “Strava Segments” (and then live segments), local legends, and now video uploads.

These features continue to improve the core transaction and build a moat around the platform. Similarly, Venmo continues to optimize how you send money (ease of finding another Venmo user, phone verification for security, etc).

Social Mechanism

For proper network effects, customers need to talk about, show off, or invite more users to the network.

This is a bigger factor than many people realize. This social mechanism can take several forms. I think of it in two (maybe, three?) large buckets:

Signaling - I want to signal something to the world.

Selfishness - You joining makes the platform better for me (and you).

Altruism (Maybe?) - I spread an idea or product because it’s innately beneficial.

(The better part of me wants to believe altruism is a factor, but maybe that’s mostly a selfish in disguise? I’d love to hear from you either way! We won’t focus on it too much here.)

Signaling as a Social Mechanism

I’ve been re-reading a post from

about signaling as a service. From the post:a) Most of our everyday actions can be traced back to some form of signaling or status seeking

b) Our brains deliberately hide this fact from us and others (self deception)

Certain apps and services lean into this signaling behavior and thus spread faster. For example, workouts are equally effective whether you log them on Strava or not, but “Strava or it didn’t happen” is still a thing. Logging a workout on Strava signals “I’m healthy” to your friends and network.

Other examples are less obvious. As Julian points out, “Sent via Superhuman” at the bottom of an email says something about the sender. CrossFitters wear gear and talk about CrossFit ad nauseam because it makes them feel cool, part of the “hardcore” crowd. The same thing is happening with a wave of apps on the ChatGPT frontier. Using them and telling friends signals “I’m tech savvy.”

“Selfishness” as a Social Mechanism

(I put “selfishness” in quotes because it has a negative connotation. I don’t think it’s inherently negative in this instance.)

I nudged our babysitter to get on Venmo so I didn’t have to pay her in cash. When we were in Oklahoma with limited reception recently, I nudged a friend to get on WhatsApp so I could message with them.

We’re incentivized to share apps and services if someone new joining benefits us.

This benefit could be very tangible. If you join Wealthfront with my link, we both get a boost in the APY for our savings account. Apps lean into this all the time.

Or, more focused on reducing fri

ction and hassle. If I’m working on a doc, it’s easier if you just join Notion since it’s much easier to collaborate. For more on this, check out this post about crossing the chasm to multi-player.

Fable is Pulling This All Together

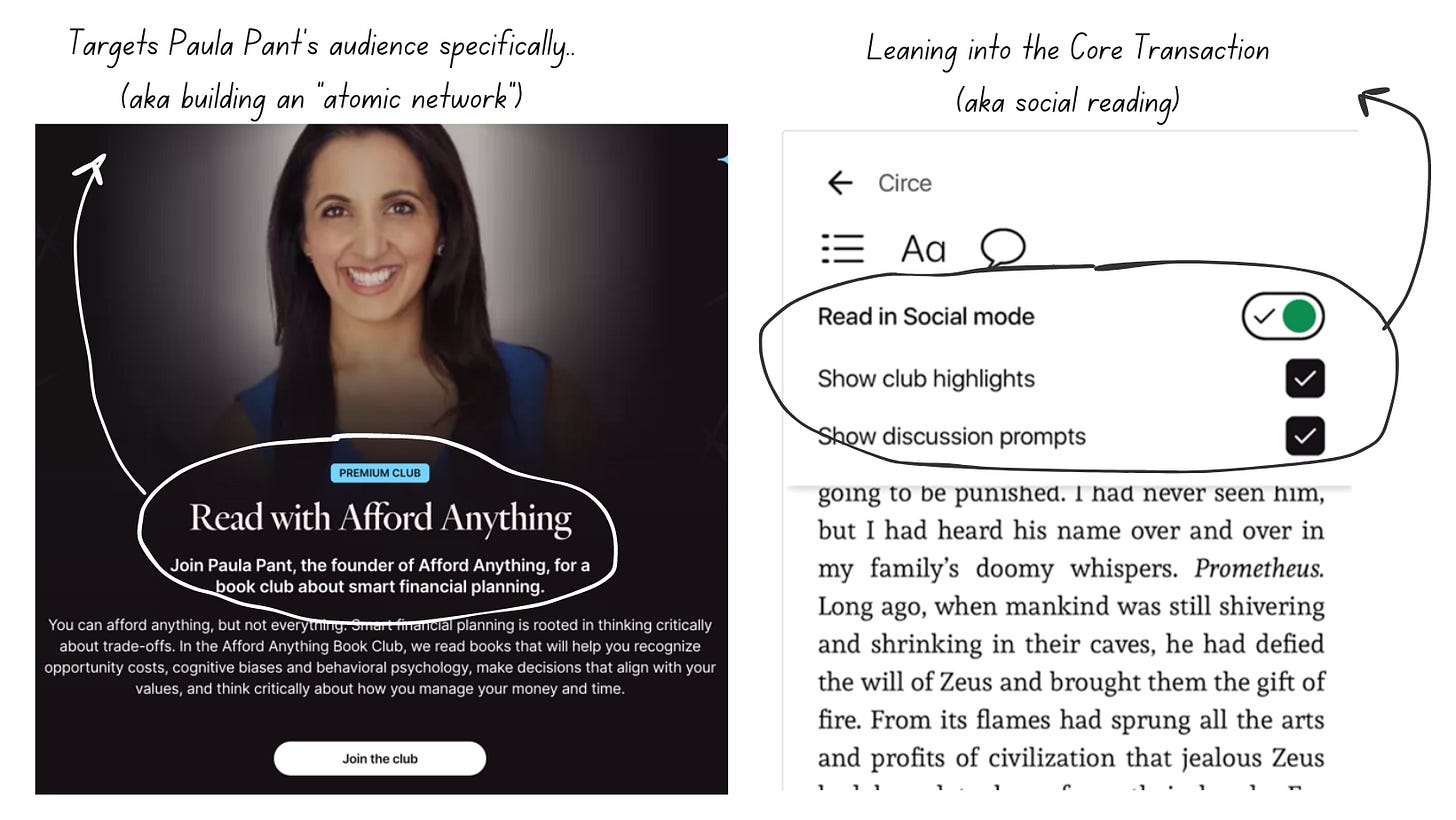

I’ve been diving into Fable - the book club app for social reading. Undoubtedly, we need a new Goodreads, but Amazon (the parent company) enjoys such a strong moat around reading that it’s hard to generate revenue. Thus, many reading-related startups end up in the graveyard.

I’m bullish on Fable for some of the reasons mentioned above. They’ve taken a different approach in building the network.

Most users join Fable because of a specific book club, often hosted by one of their favorite writers. This means they’re immediately pulled into a targeted, like-minded community (aka an atomic network). Compare this to other reading apps that aim for mass appeal from the very start. Fable, by contrast, builds niche book clubs and pulls users in.

The core transaction on Fable is book discussion. No other app or service (that I’m aware of) is doing this well. They’ve built some really great features to further enable this transaction, and I imagine they’ll continue to innovate here.

Reading has a strong social signal. People share their reading lists, book recommendations, etc without prompting.

Over to You

If you made it this far, I’d love to know what you think. Just hit reply here and let me know. If you enjoyed this one, why not share it with a friend?

Reading Across the Web

Anu Atluru provides a definition of trophy jobs based on the status-to-substance ratio. I’m on the hunt for substance.

Julian Lehr wrote about the meta-layer for notes. Really interesting ideas! “What we need instead is a spatial meta layer for notes on the OS-level that lives across all apps and workflows.”

Casey Winters wrote about how to build a successful consumer subscription business. He breaks down the difference between B2B and B2C in the context of acquisition, net dollar retention, and more.

Speaking of competitive advantages, I read this oldie-but-a-goodie from Jason Cohen (A Smart Bear) - Real Unfair Advantages. “The only real competitive advantage is that which cannot be copied and cannot be bought.”